According to the exFAT file system specification, the maximum length of a file name is 255 characters (UTF-16LE):

The FileName field shall contain a Unicode string, which is a portion of the file name. In the order File Name directory entries exist in a File directory entry set, FileName fields concatenate to form the file name for the File directory entry set. Given the length of the FileName field, 15 characters, and the maximum number of File Name directory entries, 17, the maximum length of the final, concatenated file name is 255.

This limit wasn’t really enforced in the exFAT driver of the Linux kernel, so it could be possible to craft a File directory entry set containing more than 17 File Name directory entries resulting in a concatenated file name much longer than 255 characters. And all of these characters were copied into a stack-allocated array of 258 characters.

So, here comes a stack overflow. But how to weaponize it?

Let’s get back to the vulnerable code. Here are two functions containing the vulnerability (my comments start with “//”):

static int exfat_extract_uni_name(struct exfat_dentry *ep,

unsigned short *uniname) // 'uniname' is a stack-allocated structure member containing 258 characters

{

int i, len = 0;

for (i = 0; i < EXFAT_FILE_NAME_LEN; i++) {

// EXFAT_FILE_NAME_LEN is 15 (the maximum number of characters stored in one File Name directory entry)

*uniname = le16_to_cpu(ep->dentry.name.unicode_0_14[i]);

if (*uniname == 0x0) // Stop when a null character (0x0000) is encountered in this File Name directory entry

return len; // The function returns the number of characters copied into 'uniname', could be less than 15

uniname++;

len++;

}

*uniname = 0x0;

return len;

}

static int exfat_get_uniname_from_ext_entry(struct super_block *sb,

struct exfat_chain *p_dir, int entry, unsigned short *uniname) // Again, 'uniname' is a stack-allocated structure member

{

int i, err;

struct exfat_entry_set_cache es;

err = exfat_get_dentry_set(&es, sb, p_dir, entry, ES_ALL_ENTRIES);

if (err)

return err;

/*

* First entry : file entry

* Second entry : stream-extension entry

* Third entry : first file-name entry

* So, the index of first file-name dentry should start from 2.

*/

for (i = ES_IDX_FIRST_FILENAME; i < es.num_entries; i++) {

// ES_IDX_FIRST_FILENAME is 2 (the File Name directory entries always start at this index),

// 'es.num_entries' is calculated based on the on-disk structure (the number of directory entries in this set, 256 at most)

struct exfat_dentry *ep = exfat_get_dentry_cached(&es, i);

/* end of name entry */

if (exfat_get_entry_type(ep) != TYPE_EXTEND)

break;

exfat_extract_uni_name(ep, uniname);

uniname += EXFAT_FILE_NAME_LEN;

// Note that the return value from the previous call is ignored, the 'uniname' pointer is always incremented by 15

}

exfat_put_dentry_set(&es, false);

return 0;

}So, the code iterates over a directory entry set, and for each directory entry (within the set) describing a file name, it extracts a part of this file name, and concatenates a final file name in the ‘uniname’ structure member.

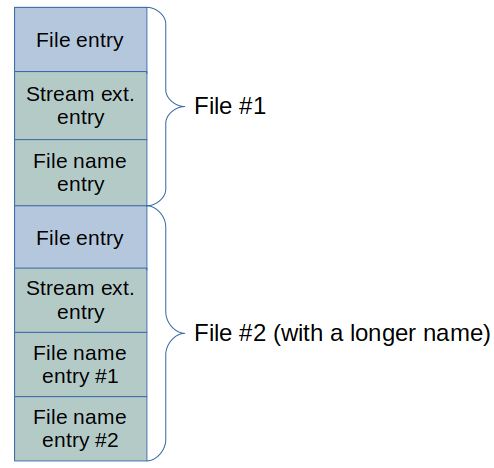

In the FAT family of file systems, each file is described by a set of directory entries, and a directory contains an array of directory entry sets describing its files and subdirectories. In the exFAT file system, a directory entry set for an ordinary file or a directory contains at least 3 directory entries (each one is 32 bytes in length), the first 2 describe the file size, the file attributes, the timestamps, the starting cluster (of the file data; for directories — file data is an array of directory entry sets), and some other metadata (see the picture above). The remaining entries in the set contain the file name and vendor-specific data, if any.

The problem is: the code assumes that the file name entries always produce a concatenated file name that fits 255 characters (the limit is 258 characters, it includes 1 additional character for a null and 2 additional characters for conversion). Storing more than 255 file name characters in a directory entry set is a file system format violation, but it’s accepted by the Linux driver, but it also results in a stack overflow (because the file name is concatenated in a stack-allocated variable).

It’s possible to craft a file name consisting of 254 entries, so the longest concatenated file name has 3810 characters. And the maximum overflow is 3810*2-258*2=7104 bytes.

This stack overflow is interesting, because it potentially allows to bypass stack canaries!

Note that the exfat_extract_uni_name() function stops copying the characters into the destination buffer once a null character (0x0000) is encountered, and returns the number of characters copied. But the caller ignores that returned value and advances the pointer by 15 characters (30 bytes) for the next iteration. Thus, it’s possible to skip (leave intact) 14 characters, or 28 bytes, in one iteration. If a stack canary is within this area, it’s left untouched.

(I was unable to exploit the vulnerability this way, so this is just a proposal.)

But there is another way to bypass the stack canary check — cause a kernel oops, which kills the current task before the canary check, but after the overflow has caused some unwanted impact.

And I was able to exploit the vulnerability this way…

In particular, my exploit overwrites a stack-allocated pointer to a null-terminated string, so the following attempt to append a terminating null character to this string actually becomes the “write a null byte to an attacker-chosen memory location” primitive. Later, but before the canary check, a null pointer dereference occurs in another location of the driver’s code, killing the kernel task exploited. So, an attacker is capable of writing a null byte at a controller memory location, without causing a kernel panic (due to the stack canary check).

The ability to write a null byte at an attacker-chosen memory offset is enough to disable some kernel protection mechanisms like the lockdown mode.

For example, if the system is in the integrity lockdown (which is automatically enabled when the Secure Boot feature is on), it can’t load unsigned kernel modules, so even a privileged user (root) has no intended way to run their code in the kernel mode (a physically-present user can overcome this restriction by enrolling the key for a custom, user-signed kernel module, but this requires some interaction during the boot).

Using the primitive described above, it’s possible to set a kernel variable controlling some security feature to zero, effectively disabling checks that rely on that variable. To load unsigned kernel modules during the integrity lockdown, an attacker must set to zero two kernel variables: sig_enforce and kernel_locked_down. (So, the exploit has to be executed twice.)

After this, any custom (unsigned) kernel module can be loaded even if the Secure Boot feature is enabled.

The KASLR feature is irrelevant here, because it doesn’t protect kernel addresses from a privileged user (root).

In the “Secure Boot restrictions bypass” scenario, an image containing a vulnerable kernel, a corresponding init script (and the exploit, of course), launching before a real operating system, is placed onto a bootable drive. When launched, this image loads a malicious (and unsigned) kernel module, which establishes its control over the kernel mode and then switches to the real operating system (for example, using the kexec call). (Privileged (root) access is required to mount such an attack.)

Here is a video demonstrating the attack against the kernel_locked_down variable: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1–E4hQoUzBTaZ8fKDgTi-LGICezhIDkz/view?usp=drive_web.

(I won’t publish a weaponized exploit.)

Is the exploit reliable?

In a virtual machine (VirtualBox), the exploit (used to reset both kernel variables mentioned above) always succeeds.

On real hardware, the success rate of the same exploit is more than 50%. In some cases, the kernel panics, because of the detected stack canary corruption (a null pointer dereference doesn’t happen in these cases).

There are two ways to improve the success rate here:

- enable the “reboot on panic” option (when the kernel crashes, the machine reboots and the exploit is launched again); or

- load a vulnerable crash kernel and use it to get a second chance (when the main kernel crashes, the crash kernel is launched and the same exploit is tried again, no reboot required here).

During the experiments, I found that the kexec call is ultimately broken: it freezes on some (but not all) hardware. But that’s another story…

Final thoughts

This vulnerability is enough to revoke the affected signed kernels. However, this is not a pre-ExitBootServices() vulnerability, so using it against the Windows operating system isn’t going to be easy, although not impossible (it’s almost impossible to kexec into Windows).

Timeline

- 2023-05-28: the vulnerability was discovered by me.

- 2023-07-07: the vulnerability was reported by me to the Linux kernel security team.

- 2023-07-13: a fix is available (but not yet merged into the official source trees).

- 2023-08-09: the vulnerability is unexpectedly disclosed by Red Hat (their description was taken from my report): https://bugzilla.redhat.com/show_activity.cgi?id=2221609.

- 2023-08-10: the kernel team tells me to give them “a few days” to merge the fix into the stable kernel versions, so my disclosure is delayed.

- 2023-08-23: this post has arrived.

5 thoughts on “CVE-2023-4273: a vulnerability in the Linux exFAT driver”