Recently, IEEE released the P1619/D12 (October 2024) draft that changes the XTS mode of operation of the AES cipher. In particular, there is a new requirement:

The total number of 128-bit blocks in the key scope shall not exceed 2^44 (see D.6). For optimum security, the number of 128-bit blocks in the key scope should not exceed 2^36 (see D.4.3).

The current limit (IEEE Standard 1619-2018) is significantly higher:

The total number of 128-b blocks shall not exceed 2^64.

The proposed soft limit means that you are recommended not to encrypt more than 1 TiB of data without changing the keys, “for optimum security”. And the proposed hard limit means that you are not allowed to encrypt more than 256 TiB of data without changing the keys (the current limit is 268435456 TiB).

This requirement makes existing full-disk encryption implementations non-compliant, as mentioned by Milan Brož and Vladimı́r Sedláček in the “XTS mode revisited: high hopes for key scopes?” paper. The authors state that the proposed standard lacks a clear threat model, as well as rules defining how keys should be generated.

When exploring possible alternatives, the authors of this paper suggest the following:

From a long-term perspective, it might be more beneficial to switch to a different (wide) encryption mode ([…]) if length-preserving ciphertext is required. Or if the storage device provides space for authentication tags, authenticated encryption would be a strong candidate as well.

So, let’s explore the XTS mode in practice, then take a look on its alternatives…

Frankly speaking, the XTS mode is controversial, because it’s susceptible to:

- Precise traffic analysis: an adversary capable of observing multiple versions of encrypted data can deduce what 16-byte blocks have changed between these versions.

- Precise randomizing attacks: an adversary can turn a specific decrypted 16-byte block into random garbage by introducing a modification to the corresponding ciphertext.

These issues are well-known: e.g., see this Wikipedia article.

In practice, both flaws are crucial to the current full-disk encryption implementations (like BitLocker and LUKS). Here are examples for the traffic analysis attacks:

- In the TPM-only mode of operation: a physically-present attacker can boot a target computer “seamlessly” up to the operating system’s login screen — thus, enabling traffic analysis attacks (new versions of encrypted data are produced due to background write activities of the operating system).

- In the TPM plus network key mode of operation (which is used to implement secure unattended boot for servers): the same traffic analysis attacks are possible too (although a target computer is required to reside in a corporate network during the attack, otherwise a password is needed to unlock the TPM-bound encryption key).

- In the TPM plus password mode of operation: if the password (i.e., one of two “factors”) is compromised, the same traffic analysis attacks are possible (the password alone isn’t enough to decrypt the data).

- Sometimes full-disk encryption is used to protect data against legitimate unprivileged users (e.g., on a corporate laptop, it’s used to “enforce” existing file system access controls): such users have physical access to target computers, but no access to the corresponding encryption keys (even if an encryption password is set, it’s not enough to obtain the necessary key — i.e., the key is bound to the TPM), although they can boot the target computer and log in to its operating system — thus, enabling similar traffic analysis attacks.

- In the dual-boot scenarios, a compromised operating system installation can be used to attack another, encrypted installation. Over time, a compromised operating system is likely to observe multiple states of the encrypted volume (of another operating system).

- Finally, some authors suggest full-disk encryption as a measure against backdoors in the HDD/SSD firmware (along with other protections — against DMA and execution of untrusted code): obviously, traffic analysis attacks are possible to some extent (although there is no much space for such a backdoor to store old copies of encrypted data). A similar scenario is the “explicit” or “implicit” network boot (e.g., explicitly via the iSCSI protocol or implicitly via launching a virtual machine using a disk image stored on a network-based file system): an attacker can control the disk image storage (e.g., the iSCSI target), but not the virtualization host (which runs the virtual machine).

These scenarios are also relevant to randomizing attacks: attackers can turn some 16-byte blocks of their choice into random garbage and then observe runtime effects of this. The first two examples demonstrate that even one-time access to a target computer (and without any kind of prior knowledge of a secret) may expose multiple versions of some ciphertext blocks to unauthenticated attackers, and they can force the operating system to decrypt some modified ciphertext blocks.

It perfectly matches the following threat model from Microsoft:

The classic solution to this problem is to run a low-level disk encryption driver with the key provided by the user (passphrase), a token (smart card) or a combination of the two. The disadvantage of the classic solution is the additional user actions required each time the laptop is used. Most users are unwilling to go through these extra steps, and thus most laptops are unprotected.

BitLocker improves on the classic solution by allowing the user actions during boot or wake-up from hibernate to be eliminated. This is both a huge advantage and a limitation. Because of the ease of use, corporate IT administrators can enable BitLocker on the corporate laptops and deploy it without much user resistance. On the downside, this configuration of BitLocker can be defeated by hardware-based attacks.

[…]

In practice, we expect that many laptops will be used in the TPM-only mode and that scenario is the main driver for the disk cipher design.

[…]

In the BitLocker attack model we assume that the attacker has chosen some of the plaintext on the disk, and knows much of the rest of the plaintext. Furthermore, the attacker has access to all ciphertext, can modify the ciphertext, and can read some of the decrypted plaintext. (For example, the attacker can modify the ciphertext which stores the startup graphic, and read the corresponding plaintext off the screen during the boot process, though this would take a minute or so per attempt.) We also assume that the OS modifies some sectors in a predictable way during the boot sequence, and the attacker can observe the ciphertext changes.

However, the attacker cannot collect billions of plaintext/ciphertext pairs for a single sector. He cannot run chosen plaintext differences through the cipher. (He can choose many different plaintexts, but they are all for different sectors with different tweak values, so he cannot generate chosen plaintext differences on a single sector.) And finally, though this is not a cryptographic argument, to be useful the attack has to do more than just distinguish the cipher from a random permutation.

(Source.)

It should be noted that some vendors use a more “strict” threat model, which explicitly excludes traffic analysis attacks, as well as any kind of ciphertext manipulation:

Note to security researchers: If you intend to report a security issue or publish an attack on VeraCrypt, please make sure it does not disregard the security model of VeraCrypt described below. If it does, the attack (or security issue report) will be considered invalid/bogus.

[…]

VeraCrypt does not:

[…]

Preserve/verify the integrity or authenticity of encrypted or decrypted data.

[…]

Prevent an attacker from determining in which sectors of the volume the content changed (and when and how many times) if he or she can observe the volume (unmounted or mounted) before and after data is written to it, or if the storage medium/device allows the attacker to determine such information (for example, the volume resides on a device that saves metadata that can be used to determine when data was written to a particular sector).

(Source.)

In other words, even the capability of injecting malicious, non-random data into the encrypted volume isn’t a vulnerability here, despite the XTS mode guarantees… But users expect such protections!

Without the Elephant diffuser, an attacker with physical access to the encrypted disk and with knowledge of exactly where on the disk target files are located could modify specific scrambled bits, which will in turn modify the targeted files in an exact way when the disk is later unlocked. For example, they could modify one of the programs that runs while Windows is booting up to be malicious, so that the next time the user unlocks the disk and boots Windows, malware automatically gets installed. The Elephant diffuser prevents this attack from working. With the diffuser, an attacker can still modify scrambled bits, but doing so will prevent them from having fine-grained control over exactly what changes they make when the disk is unlocked. Rather than being able to make specific programs malicious, they are more likely to scramble large chunks of programs and simply cause the computer to crash instead of getting hacked.

[…]

Removing the Elephant diffuser doesn’t entirely break BitLocker. If someone steals your laptop, they still won’t be able to unlock your disk and access your files. But they might be able to modify your encrypted disk and give it back to you in order to hack you the next time you boot up.

(Source.)

Precise traffic analysis and precise randomizing attacks lead to vulnerabilities like CVE-2025-21210 (also known as CrashXTS). And that vulnerability wouldn’t exist if any other cipher mode suitable for storage encryption was used (a poor granularity of data modification leaks is enough to render the vector unexploitable).

In short, this vulnerability is divided into two parts. First, it allows a physically-present, unauthenticated attacker to find the exact ciphertext block holding a reference to a driver that encrypts hibernation images while they are written to the underlying storage device (observing four states of the encrypted drive is enough to achieve this). Second, after corrupting this reference (by changing any bit in that ciphertext block), this driver is no longer loaded during the boot, so the operating system starts writing hibernation images in cleartext (and the attacker can hibernate the target computer while at the login screen, there is no need to authenticate).

Therefore, wide-block ciphers and wide-block modes are expected to mitigate precise traffic analysis and randomizing attacks.

For example, this is what Phillip Rogaway wrote:

A crucial question we have only just skirted is whether or not it actually makes sense to use a narrow-block scheme, XTS, instead of a wide-block one, like EME2, because the former needs less computational work. The computational savings is real — one can expect EME2 to run at about half the speed of XTS. But the security difference is real, too, and harder to quantify. The question of whether the tradeoff is “worth it” is more a security-architecture question than a cryptographic one, and the answer is bound to depend on the specifics of some product. Yet if one is going to be reading or writing an entire data-unit, spending more work than to ECB-encipher it already, it seems likely to be preferable to “do the thing right” and strong-PRP encipher the entire data unit. Were I consulting for a company making a disk-encryption product, I would probably be steering them away from XTS and towards a wide-block scheme. “Too expensive” is a facile complaint about bulk encryption, but often it’s not true.

Attackers won’t be able to track changes to encrypted data in a fine-grained way — they can tell what data units* have changed between two versions of encrypted data, but there is no way to track these changes with the granularity of 16-byte blocks like in the XTS case. Similarly, randomizing attacks aren’t precise too — a single change to the ciphertext turns the corresponding decrypted data unit* into random garbage, not just the 16-byte block as in the XTS case.

* — data units are sectors of traditional storage devices (like HDDs and SSDs), which are 512 or 4096 bytes in size (as exposed to the host); some implementations can encrypt data units spanning across multiple sectors (e.g., on a battery-backed RAID device), this further reduces the risks of traffic analysis and randomizing attacks.

However, there is one caveat: even with a very poor granularity, randomizing attacks may lead to arbitrary code execution…

This is rather surprising, but overwriting 10 MiB (or 16 MiB, or even more) of encrypted data to turn its decrypted form into random garbage can be enough for that!

One example is shown in the second part of my paper (no CVE number assigned), another example is CVE-2025-4382.

In both cases, physically-present, unauthenticated attackers target LUKS-encrypted operating system volumes which are unlocked automatically during the boot using the TPM-bound key. These attacks don’t require offset guessing or traffic analysis, because data to be randomized is located at a predefined, documented offset — i.e., this is a file system superblock (header).

By turning this superblock into random garbage (and, therefore, making the file system unrecognizable), attackers force some boot components to misbehave:

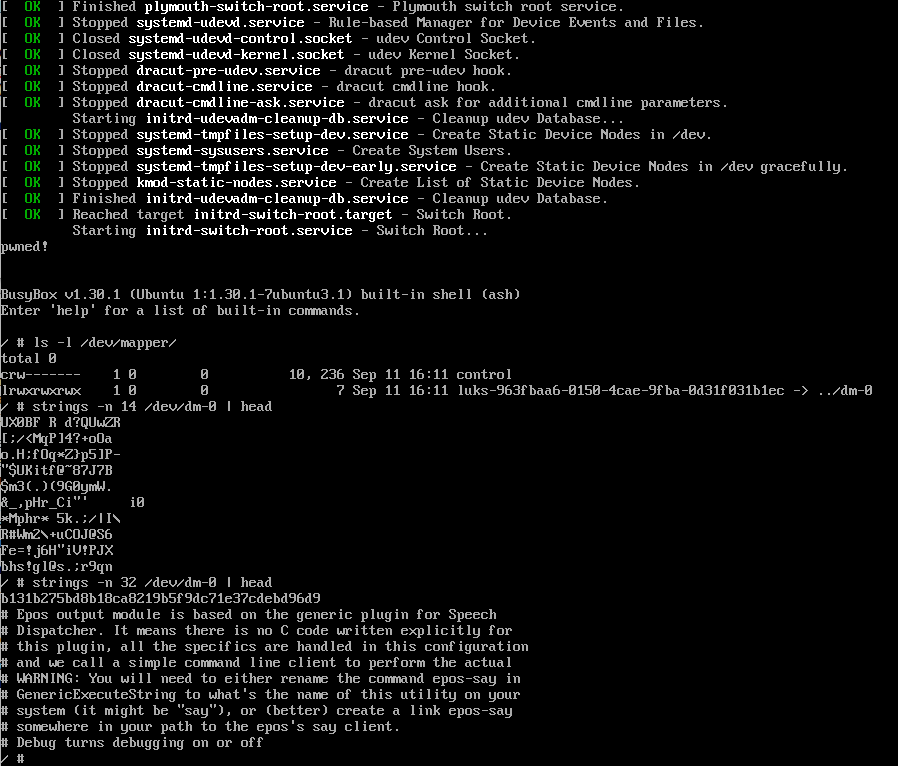

- In the first example, dracut (a set of programs for the initial RAM file system used to boot Linux-based operating systems) picks a wrong, unencrypted, attacker-controlled file system (on an attached external drive) to continue the boot and starts the init program from it, while the encryption key is in memory.

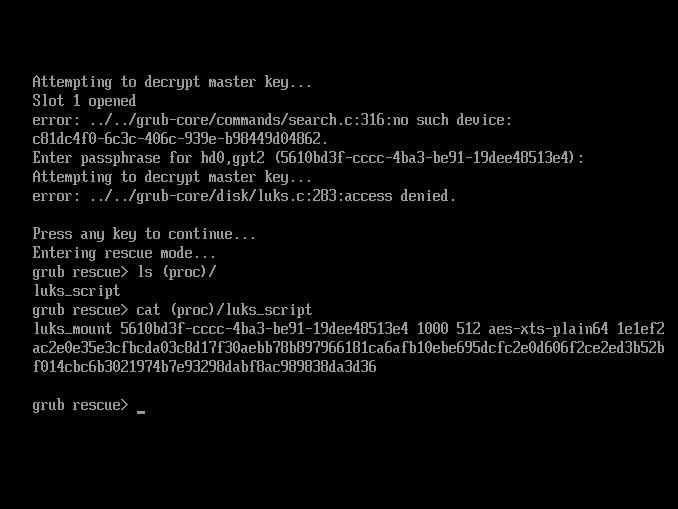

- In the second example — CVE-2025-4382, GRUB (a boot manager, which is more an operating system than a boot loader) spawns its rescue shell while the encryption key is in memory and can be easily displayed (via the cat command).

As you can see, three vulnerabilities described in this post are caused by programs failing to read something. And only one of them, CVE-2025-21210 (CrashXTS), can be mitigated through the use of wide-block ciphers or wide-block modes. And none of them requires planting specific plaintext values through the ciphertext manipulation (i.e., the attacker wants a corruption with random data, but not some specific byte patterns in the decrypted form). And none of them requires successful user authentication.

Under the Common Weakness Enumeration list, these vulnerabilities can be mapped to CWE-636: Not Failing Securely (‘Failing Open’).

If unprivileged but physically-present users are within the threat model, the attack surface increases: such users can try to escalate their privileges through corruption of file system security descriptors, firewall rules, etc. And companies already use full-disk encryption (relying on the TPM) for this kind of protection!

Consequently, this means that a failure to open something security-relevant (a file, or a directory, or a file system itself) is critical to handle properly when the full-disk encryption is enabled. Of course, these and similar vulnerabilities can be fixed individually, but the bigger problem is still here — failure to open (or read, or parse) something should be reliably detected.

And authenticated modes seem to provide a solution for this problem…

In this mode of operation, each encrypted data unit has a tag (a message authentication code), which is used to verify (authenticate) its bytes (either the ciphertext, if the encrypt-then-MAC approach is used, or the plaintext, if the MAC-then-encrypt approach is used).

The disk encryption driver uses these tags to authenticate data before returning its decrypted form to the reader. This defeats the randomizing attack as well as any other ciphertext manipulation. (Also, these tags consume space, so the usable storage size is lower, this is a trade-off for security.)

And, again, there is one caveat: data units that failed integrity authentication can be more dangerous than random chunks of data!

What happens when a data unit to be read fails the integrity authentication? There are four possible outcomes:

- This data unit is decrypted normally and returned as is. The error is logged somewhere.

- This data unit is treated as corrupted, the I/O error (or a similar error code) is returned to the reader.

- The operating system crashes (panics) immediately. There is a security violation, so code execution must stop.

- The operating system reboots immediately. Similar to the above, but a graceful shutdown is performed.

The first option is useful for data recovery, but not suitable for any kind of production use, because data authentication is effectively disabled this way.

The second option is the one implemented in Linux and FreeBSD (for the authenticated disk encryption modes):

[…] if the attacker modifies the encrypted device, an I/O error is returned instead of random data.

(Source.)

When data corruption/modification is detected, geli will not return any data, but instead will return an error (EINVAL).

(Source. Note: since 2020, the actual error code returned is EINTEGRITY.)

The last two options might cause boot loops (when a corrupted data unit is accessed during every boot, causing endless fatal errors and subsequent reboots) and they aren’t friendly to silent, non-malicious data corruption events (which can be caused by faulty storage devices, bad memory, kernel bugs, and other non-malicious errors).

Occasionally, users will slowly opt out of these two options, especially when one “random” corrupted data unit causes reboots and excess warnings. In the Android world, a similar corruption affecting an unencrypted but integrity-protected file system causes a reboot, which switches the device into the “report I/O errors instead” mode to avoid boot loops, and displays a warning.

Back to the second option: reporting data corruptions as I/O errors (or similar errors) is the most dangerous way, but how? (Now, let’s assume that attackers know what sectors they need to modify to achieve something.)

1. Many applications and libraries are written in a way that doesn’t distinguish between I/O errors and expected conditions (e.g., end-of-file).

Let’s take a look at the following code:

// 'f' is a large (multisector) configuration file opened via the fopen() call.

// It contains "name = value" (or similar) pairs defining some security-related options...

while (getline(&line, &cnt, f) != -1) {

// Parse the 'line' to get a configuration value, then use it...

}

According to the documentation, the getline() function returns -1 when the end-of-file is met (this is an expected condition) or when an I/O error is encountered. The code above doesn’t distinguish between these conditions (i.e., it doesn’t check the errno variable), so an attacker can “cut” (reduce the number of “fetchable” lines of) the configuration file by modifying one of its sectors.

Thus, instead of giving random bytes to the parser (like in the XTS mode, when a ciphertext block is altered), the attacker “truncates” the file data (as “seen” by the code above) by changing one bit in the corresponding nth sector (which causes the I/O error after the sector data authentication failure).

Another example: a configuration parser implemented in CPython — its read() method skips a supplied configuration file when an I/O error (or any other operating system error) is encountered:

def read(self, filenames, encoding=None):

"""Read and parse a filename or an iterable of filenames.

Files that cannot be opened are silently ignored; this is

designed so that you can specify an iterable of potential

configuration file locations (e.g. current directory, user's

home directory, systemwide directory), and all existing

configuration files in the iterable will be read. A single

filename may also be given.

Return list of successfully read files.

"""

if isinstance(filenames, (str, bytes, os.PathLike)):

filenames = [filenames]

encoding = io.text_encoding(encoding)

read_ok = []

for filename in filenames:

try:

with open(filename, encoding=encoding) as fp:

self._read(fp, filename)

except OSError:

continue

if isinstance(filename, os.PathLike):

filename = os.fspath(filename)

read_ok.append(filename)

return read_ok(Source.)

A chunk of random data will cause the parser to raise an exception, but the I/O error forces the parser to silently skip the existing configuration file (and the parsed configuration will be empty, if no other valid configuration file was supplied to the method).

2. File system drivers can suppress I/O errors or turn them into other error codes (e.g., ENOENT)

Let’s take a look at the following file system parsing code (taken from the Linux FAT driver):

static int fat__get_entry(struct inode *dir, loff_t *pos,

struct buffer_head **bh, struct msdos_dir_entry **de)

{

struct super_block *sb = dir->i_sb;

sector_t phys, iblock;

unsigned long mapped_blocks;

int err, offset;

next:

brelse(*bh);

*bh = NULL;

iblock = *pos >> sb->s_blocksize_bits;

err = fat_bmap(dir, iblock, &phys, &mapped_blocks, 0, false);

if (err || !phys)

return -1; /* beyond EOF or error */

fat_dir_readahead(dir, iblock, phys);

*bh = sb_bread(sb, phys);

if (*bh == NULL) {

fat_msg_ratelimit(sb, KERN_ERR,

"Directory bread(block %llu) failed", (llu)phys);

/* skip this block */

*pos = (iblock + 1) << sb->s_blocksize_bits;

goto next;

}

offset = *pos & (sb->s_blocksize - 1);

*pos += sizeof(struct msdos_dir_entry);

*de = (struct msdos_dir_entry *)((*bh)->b_data + offset);

return 0;

}(Source.)

The fat__get_entry() function is responsible for fetching next directory entries (when listing a directory via the readdir() calls). If this function encounters an unreadable sector, it skips to the next one.

Here is an example of a FAT directory without I/O errors (ls -l):

total 1600

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 100.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 101.txt

[…]

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 198.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 199.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 19.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 1.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 13 Mar 12 23:08 200.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 201.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 202.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 203.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 204.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 205.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 206.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 207.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 208.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 209.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 20.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 210.txt

[…]

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 9.txtAnd the same directory with one I/O error somewhere in the middle:

total 1568

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 100.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 101.txt

[...]

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 198.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 199.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 19.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 1.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 208.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 209.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 20.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 210.txt

[...]

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5 Mar 12 23:05 9.txtThus, an attacker can “cut” the directory, making some files “invisible” (from 200.txt to 208.txt in the example above, other entries, including those in the beginning and at the end of the directory, aren’t affected), while the readdir() calls don’t indicate any errors.

The kernel log, however, contains some relevant messages:

[35709.839349] FAT-fs (dm-0): Directory bread(block 5689) failed

[35710.139497] FAT-fs (dm-0): Directory bread(block 5689) failed

[35710.149530] FAT-fs (dm-0): Directory bread(block 5689) failed

[35710.149624] FAT-fs (dm-0): Directory bread(block 5689) failed

[35710.149674] FAT-fs (dm-0): Directory bread(block 5689) failed

[35710.149718] FAT-fs (dm-0): Directory bread(block 5689) failed

[35710.149762] FAT-fs (dm-0): Directory bread(block 5689) failed

[35710.149810] FAT-fs (dm-0): Directory bread(block 5689) failed

[35710.149856] FAT-fs (dm-0): Directory bread(block 5689) failed

[35710.149901] FAT-fs (dm-0): Directory bread(block 5689) failedThere is another example: the Linux SquashFS driver suppresses I/O errors when reading a directory index, so unreadable directories appear as empty.

[...]

while (dir_count--) {

/*

* Read directory entry.

*/

err = squashfs_read_metadata(inode->i_sb, dire, &block,

&offset, sizeof(*dire));

if (err < 0)

goto failed_read;

size = le16_to_cpu(dire->size) + 1;

/* size should never be larger than SQUASHFS_NAME_LEN */

if (size > SQUASHFS_NAME_LEN)

goto failed_read;

[...]

if (!dir_emit(ctx, dire->name, size,

inode_number,

squashfs_filetype_table[type]))

goto finish;

ctx->pos = length;

}

}

finish:

kfree(dire);

return 0;

failed_read:

ERROR("Unable to read directory block [%llx:%x]\n", block, offset);

kfree(dire);

return 0;

}(Source.)

As you can see, when a read error is encountered, the code jumps to the failed_read label, which logs the error and returns 0 (no error), suppressing the original error code.

Update (2025-06-02): another example (a directory read error is suppressed by the kernel’s SMB client, although properly delivered over the network, and partial directory data is returned).

Update (2025-06-05): what about implementations of programming languages suppressing directory read errors of any kind? Here: Perl’s readdir() implementation doesn’t report errors!

Update (2025-06-11): one bug in ls results in integrity errors being suppressed!

My conclusion: disk encryption code that reports I/O errors (or similar error codes) for data authentication failures gives attackers a powerful tool to “truncate” files and “cut” (or “empty”) directories. In other words, returning random bytes for altered ciphertext blocks can be better than returning I/O errors to programs (including file system drivers as demonstrated above) that don’t handle them correctly. And, obviously, there is no way to fix all of these issues one by one (because the kernel code and so many userspace applications and libraries are affected). These issues have to be accounted in the threat model of the disk encryption implementations.

Failing outside the encryption layer

1. Even more, when data authentication failures cause kernel panics or reboots (the most secure and the most annoying configuration), attackers can bypass that by causing the I/O error below the disk encryption driver. In particular, they can send the Write Uncorrectable command to the underlying drive — to mark an attacker-chosen sector as unreadable, (and most ATA, SCSI, NVMe drives support it).

These I/O errors are hard to treat as data authentication failures, because the underlying storage stack can emit legitimate (non-malicious) I/O errors, either transient or permanent, which are indistinguishable from those made through the Write Uncorrectable command (which are considered as malicious here).

According to this study, latent sector errors (i.e., those identified by the drive and reported to the host) occur more often than checksum mismatches (i.e., data errors detected using additional integrity blocks) — this means that treating any I/O error as a data authentication failure seems to be overkill. Additionally, thermal shutdowns, RAID controller resets, and other sources of sudden errors must be accounted when treating I/O errors as data authentication failures: to not make things worse by panicking the kernel (or forcing the reboot) under “known extreme” conditions (in other words, creating a new critical error while trying to handle another critical error).

The situation seems to be more threatening when dealing with unencrypted, integrity-protected, read-only file systems, like /usr in some Linux distributions. Since such a file system is unencrypted, attackers know what sectors belong to security-relevant executables and configuration files. And even under these conditions, kernel developers argued that “userspace application must process it [an I/O error] in error path“, that I/O errors are not a data corruption.

Certainly, there is a lot of work on the software side. Probably, we should include I/O errors into the threat model of authenticated full-disk encryption, and distinguish between validation failures when reading files (and traversing directories) marked as critical (e.g., executables, system-wide configuration files, swap files) and files marked as non-critical (e.g., user files like documents and pictures).

2. Encrypted sectors with authentication data stored somewhere don’t protect against the partition resize. For example, in FreeBSD, GELI metadata footer isn’t authenticated**, despite its sensitive nature: it includes the “underlying device size” field (md_provsize), as well as encryption- and authentication-related fields (like md_ealgo and md_aalgo):

struct g_eli_metadata {

char md_magic[16]; /* Magic value. */

uint32_t md_version; /* Version number. */

uint32_t md_flags; /* Additional flags. */

uint16_t md_ealgo; /* Encryption algorithm. */

uint16_t md_keylen; /* Key length. */

uint16_t md_aalgo; /* Authentication algorithm. */

uint64_t md_provsize; /* Provider's size. */

uint32_t md_sectorsize; /* Sector size. */

uint8_t md_keys; /* Available keys. */

int32_t md_iterations; /* Number of iterations for PKCS#5v2. */

uint8_t md_salt[G_ELI_SALTLEN]; /* Salt. */

/* Encrypted master key (IV-key, Data-key, HMAC). */

uint8_t md_mkeys[G_ELI_MAXMKEYS * G_ELI_MKEYLEN];

u_char md_hash[16]; /* MD5 hash. */

} __packed;** — it’s MD5-hashed (see the md_hash field), but this hash can be simply recalculated against attacker-modified values.

By reducing the size of the corresponding partition, copying the original metadata footer to the last sector of the resized partition, adjusting the “underlying device size” field (md_provsize) and recalculating the hash value (md_hash) in that block, it’s possible to reduce the “visible” encrypted data size without triggering data authentication failures.

Hopefully, this issue isn’t exploitable. A “reduced” file system will be treated as corrupted, but FreeBSD is known to store some on-disk structures (like a software RAID metadata footer) in the last sector of a partition, so it’s possible to remove such a footer, and… I don’t know!

What if a GELI-encrypted file system contains a downloaded file and some of its bytes match (mimic) the format of the software RAID metadata footer? And the “new” last sector (of the corresponding encrypted partition) points exactly to these bytes? This turns a part of a user-downloaded file into the RAID metadata! However, the attacker must be able to deliver that file into the encrypted file system and, besides that, they must know its exact on-disk location, which seems unrealistic…

Another possible attack is to turn all decrypted data into “authenticated garbage”. Since encryption-related metadata isn’t authenticated in the GELI footer, it’s possible to change the encryption algorithm and mode specification (md_ealgo) — e.g., by changing it from AES-XTS to AES-CBC.

This would randomize decryption results for all encrypted sectors, while their contents remain authenticated, because GELI authenticates the ciphertext, not the plaintext. This outcome may trigger something similar to CWE-636-style bugs, although out-of-the-box GELI usage scenarios aren’t affected (or, at least, there is no obvious exploitation path for usual FreeBSD usage scenarios, which don’t support TPM-based unlocking).

The only affected configuration styles are GCONCAT-on-GELI and similar, where two or more GELI volumes are used to provide one logical device (e.g., using “concatenation”). In these cases, randomizing decrypted data on one GELI device will affect only one part of that resulting logical device. (But the GELI-on-GCONCAT scheme, which is unaffected, seems more reasonable.)

These are good reasons to validate even “benign” metadata fields! I made a feature request here.

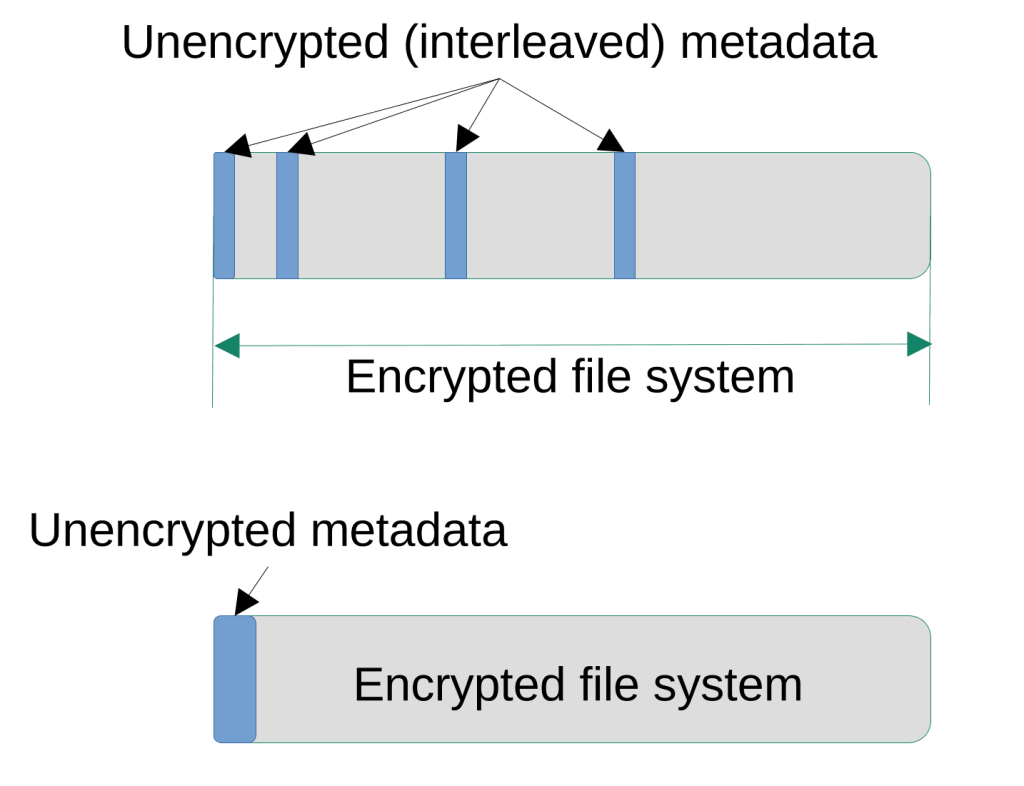

3. Some disk encryption implementations use interleaved unencrypted metadata to describe encrypted volumes.

This means that an encrypted file system and its corresponding partition (or a container file) have the same size, all necessary metadata (which is defining, at least, a cipher, its mode, and an encrypted volume key) is stored within that file system, but in the unencrypted form (this is opposed to containerized storage, when metadata is stored within the corresponding partition or file before or after the encrypted file system, and detached storage, when metadata is moved to another location like a file or a different partition).

The layouts, interleaved unencrypted and containerized unencrypted, respectively, are shown below:

When the interleaved storage is used, encryption metadata (marked in blue) is stored somewhere in the area designated for the encrypted file system (marked in grey). These locations can be accessed by reading data blocks from the mounted (unlocked) encrypted file system, but they are represented by the encryption driver as containing null bytes only (it makes no sense to actually decrypt plaintext metadata using a volume key). Additionally, these metadata areas are marked as allocated in the encrypted file system, so they can’t be overwritten by filling it with files.

When the containerized storage is used, encryption metadata is stored either in a header (blue) or footer outside of the file system area (grey), there is no way to access this location by reading data blocks in the mounted encrypted file system (i.e., it’s similar to the RAID metadata block on a drive).

BitLocker uses interleaved unencrypted storage, while LUKS supports containerized or detached one.

When the interleaved unencrypted storage is used, it’s essential to authenticate encryption metadata. All metadata must be authenticated, including metadata locations themselves.

In the BitLocker case, unencrypted metadata of a volume consist of one header (which is the first sector of the encrypted file system) and three metadata blocks (each one occupies multiple sectors somewhere in the middle of the encrypted file system). The header references the locations of these metadata blocks.

These metadata blocks are hashed (using SHA-256) and the resulting digest is encrypted (using AES-CCM). If the calculated digest doesn’t match the decrypted one, the encrypted volume is considered to be corrupted.

According to Microsoft:

In “OS Boot”, the legitimate BOOTMGR transitions to an active role to protect the VMK. The legitimacy of the BOOTMGR has been proven (above) implicitly by the fact that it has the VMK for a given volume. BOOTMGR must transition to the OS Loader, and it must do so without giving the VMK to the wrong OS Loader. This is where things get interesting. The metadata associated with the OS Volume contains a set of requirements indicating what boot executables are considered valid – more than one is required to support memory testing and to support resume from hibernate. BCD policy is also stored to ensure most BCD settings cannot be modified. To ensure the metadata is not tampered with, a MAC exists. Calculating the MAC requires knowledge of the VMK.

(Source.)

There is one caveat: the boot loader doesn’t validate this digest when the encryption key isn’t unsealed using the TPM (the kernel-mode driver always validates the digest, regardless of the protector type). So, the attacker can move the metadata blocks (while keeping the encryption-related fields intact, so the encrypted volume metadata remains valid) across the encrypted volume and the boot loader, under specific circumstances, won’t detect that.

Since these metadata areas are treated as containing null bytes after the encrypted file system is unlocked, this means that the attacker can zero arbitrary locations for the boot loader (when the key isn’t bound to the TPM).

This bug was introduced in Windows Vista, along with the first BitLocker implementation.

Fortunately, it’s not exploitable. The only “sensitive” files read by the boot loader that aren’t integrity-protected belong to the SYSTEM hive. Thus, attackers can zero some large parts of the SYSTEM hive (of their choice), but this can’t be used to leak the encryption key or some parts of decrypted file system data. And, obviously, the “seamless” boot isn’t affected at all (when the encryption key is unsealed using the TPM, the digest is validated by the boot loader properly), so one-time access leads to one attack attempt.

And, unfortunately, third-party implementations (dislocker and cryptsetup’s bitlk) don’t validate these digests. This makes them vulnerable, but the root cause is that BitLocker on-disk structures are proprietary (undocumented) — you can’t implement such protections if you are unaware of them.

Update (2025-10-10): the cryptsetup’s implementation now validates the digest!

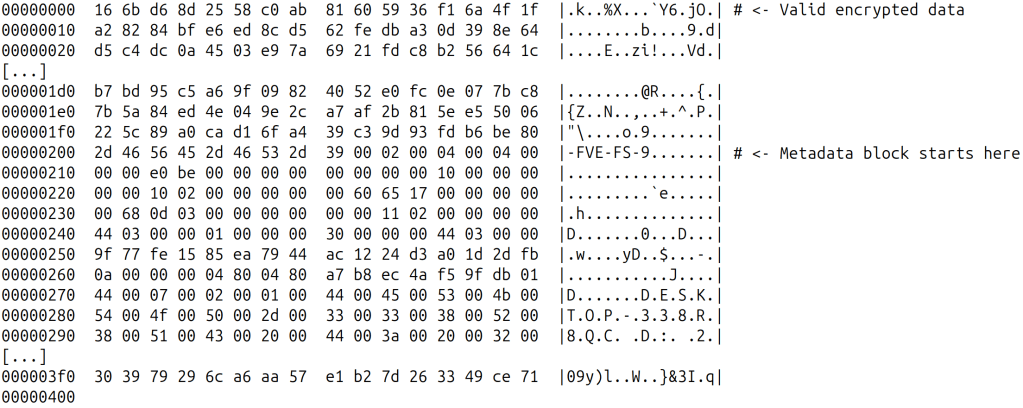

Here is an example…

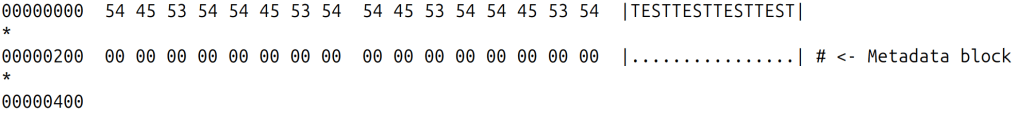

Two raw sectors somewhere in the middle of the encrypted drive:

These sectors in the decrypted form (as returned when opened using the cryptsetup’s bitlk module):

According to the threat model defined for the Elephant diffuser:

The attacker succeeds if he can modify a ciphertext such that the corresponding plaintext change has some non-random property.

(Source.)

Here, “some non-random property” is exposed by the implementation, not by the underlying crypto. Still, it’s here, also affecting other modes (because this is an implementation bug).

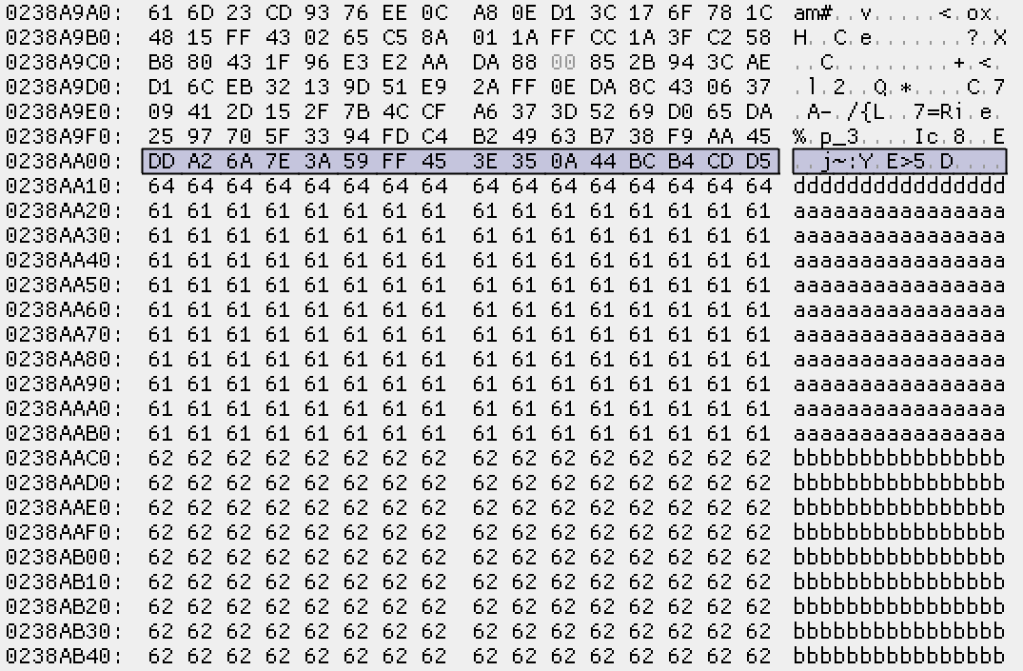

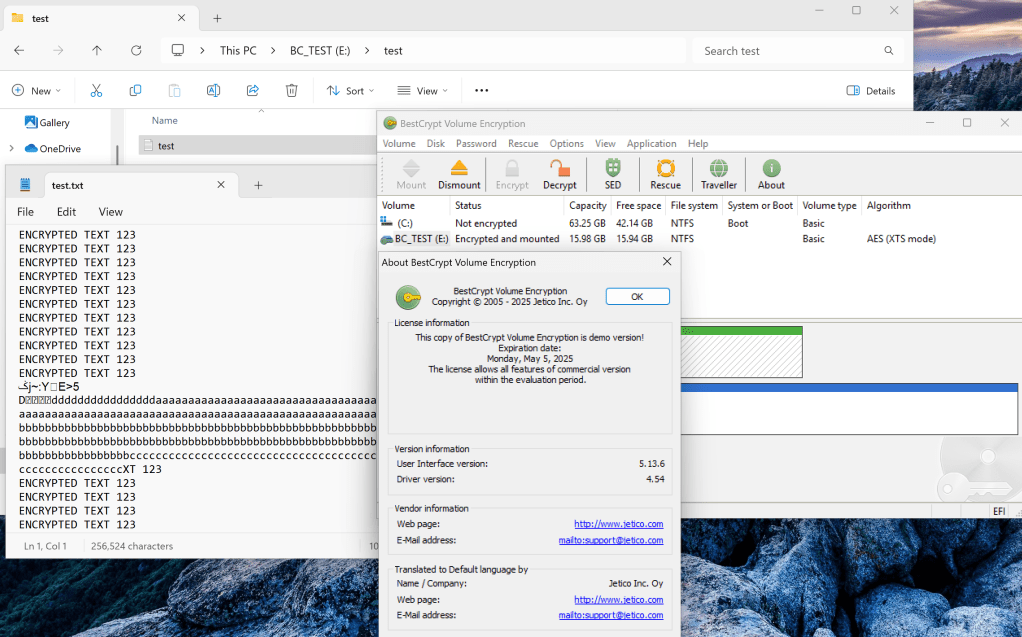

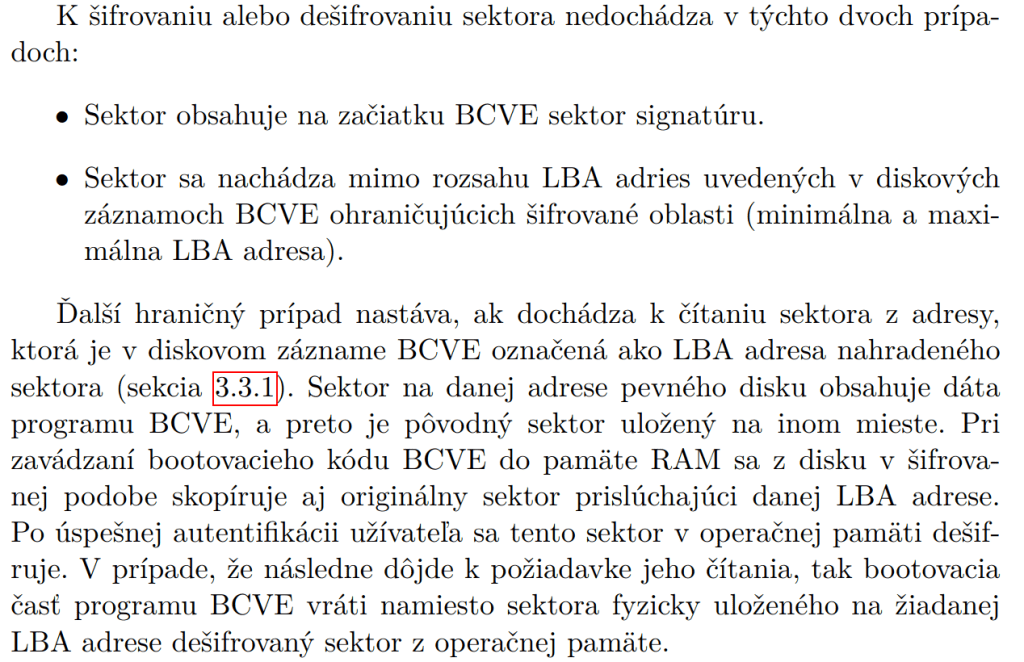

4. Finally, at least one full-disk encryption solution is known to entirely break the XTS mode guarantees… BestCrypt Volume Encryption (BCVE)!

The BCVE’s filter driver doesn’t decrypt sectors that start with a specific 16-byte signature. Instead, the driver returns these sectors as is (bypassing the actual decryption routine).

This signature is used to mark sectors containing encryption metadata, so it’s not turned into garbage when read from a mounted encrypted volume (otherwise, unencrypted metadata would become garbage when decrypted). However, an attacker can replace any encrypted sector with data starting with this signature (but having no proper encryption metadata, because only the signature is checked), forcing the filter driver to “inject” attacker-controlled, non-random data into the mounted encrypted volume.

This behavior was documented in 2016, in this paper (see section 3.3.4 and algorithm 3.7). However, no security implications were mentioned.

In 2017, security implications of this flaw were mentioned in this paper (“The Exclude Signature Vulnerability”, by Jan Vojtěšek).

Of course, if the threat model doesn’t include legitimate users reading attacker-modified ciphertext from the disk, this isn’t a vulnerability (but, obviously, no XTS key scopes are needed too in such a threat model, and many other attacks become void too).

In this old article, BestCrypt is suggested as a better alternative to BitLocker (which was using AES-CBC without Elephant diffuser at that time). The ability to inject such plaintext data directly into the encrypted volume is much worse than bit flips possible in the AES-CBC mode!

According to IEEE Standard 1619, “[t]he XTS-AES transform was chosen because it offers better protection against ciphertext manipulations“. But at least one vendor throw that protection away… The “underlying crypto” is “compliant”, but there is a way to bypass the decryption function and pass attacker-controlled data directly to the mounted volume.

In 2025, I asked Jetico about the AES-XTS guarantees in their implementation (ticket #45490), the reply was:

Let me list several scenarios:

1). We create file started with the bytes of BCVE signature.

First 512 bytes of the file will be stored on the disk in not encrypted form. We can do that intentionally, or it can happen accidentally. Please note that the probability of the event of getting these 16 bytes and exactly at the physical sector boundary is very low.2). We intentionally write the signature to the some physical sector bytes.

What we will be able to read is the same bytes in the user mode after mounting the disk volume, because BCVE will not decrypt the sector. But you can see the same data without mounting the volume at all. It appears that exploiting the effect will not help in breaking encryption of other sectors.

The sector having these 16 bytes is simply ignored by BCVE. BCVE ignores them in the same way as neighborhood sectors of another not-encrypted volume on the same physical disk.

You wrote that “This outcome is worse than the bit-flipping attack against AES-CBC”.

What we have is that the sectors not processed by BCVE. If so, what is the difference between AES-CBC (if it were used) or AES-XTS encryption, or whatever else algorithm used by the software, if such an algorithm does not run at all?

Or, may be you mean that skipping encryption of individual sector somehow affects neighborhood encrypted sectors?

And their further clarification:

I think you are correct saying that XTS mode is perfect in case of modification encrypted data to avoid the risk of getting “almost correct” but modified plain data after decryption.

Let us imagine that XTS mode would work so that it refuses to decrypt data if it was modified. For example, you speak with someone over encrypted channel. If someone in the moddle modifies even one bit of your communication, decryption on your side stops working. Will it compromize security of the channel? We don’t think so, and I hope you will agree with us.

This example is close to our case. If you place BCVE signature to some encrypted sector, it means that you have turned off decryption of the data. You will always have the same encrypted sector that is not even will be attempted to be decrypted. You have modified the sector and BCVE decryption engine with its XTS mode stops paying attention to it.

(The screenshot is here.)

Their analogy: injection of plaintext data into a TLS-encrypted connection… And, no, an unencrypted packet isn’t discarded and it doesn’t abort the connection, it’s just processed as the encrypted one, but skipping the decryption part, without any indication that this connection is only partially encrypted. Not an issue? Really?

And, besides that, they have confirmed the watermarking attack on the BCVE’s implementation! Placing an attacker-controlled file in such a way that its first 16 bytes start at the sector boundary is very easy, because, in the NTFS file system, non-resident data (i.e., files larger than 1000 bytes in most cases and files larger than 4000 bytes in all cases) always starts at the sector boundary! (This attack is possible, because these 16 bytes make the sector data bypass the encryption routine, leaving it unencrypted, which is more than enough for watermarking.)

Finally, if an attacker can spray these 16 bytes into a database (e.g., by repeatedly inserting rows or documents containing this byte pattern through a public-facing web application running on an FDE-enabled server), it’s possible to leak nearby database records (located within the same sector) to the drive in the plaintext form (just like this: an SQLite3 database file using UTF-16LE, this file as stored on the disk).

This is extremely awkward… And this behavior can be traced back to the Windows XP version of BCVE, so the implementation became broken many years ago… And Jan Vojtěšek urged Jetico to fix this vulnerability in 2017!

Update (2025-10-24):

Okay, here is another product that breaks the XTS mode guarantees slightly… It’s VMware Workstation (version tested: 17.6.4).

When a virtual disk (*.vmdk) is encrypted using the XTS mode, virtual disk sectors that are marked with zeroes in the Grain Table are always read as containing null bytes only. The proper behavior should be: return decrypted null bytes, which is just random garbage.

The Grain Table is a structure that links a sector number, as seen by a virtual machine (e.g., LBA 0), to a file offset within the VMDK image.

This means that an attacker can mark arbitrary sectors as containing null bytes only, which is impossible through ciphertext manipulations. The root cause is: if a given virtual sector has no corresponding VMDK offset (i.e., it’s unallocated in the VMDK file), the decryption routine is skipped and null bytes are returned (to a virtual machine) explicitly.

Some full-disk encryption software issues Trim requests to mark sectors belonging to an encrypted file system as deallocated (thus, leaking the entire allocation map of that encrypted file system). This bug is exactly the opposite: deallocated virtual sectors turn into null bytes in the attached encrypted virtual disk!

One thought on “Disk encryption: wide-block modes, authentication tags aren’t silver bullets”